Where Buildings Have Names : Conversations on architecture and memory

A Conversation with Adam Kołodziej

Architect, General Designer in Miastoprojekt Toruń (1972-1985)

After Mr Kolodziej’s passing in July 2025, the format of this conversation changed.

My focus shifted toward capturing the depth of detail, the atmosphere of our meeting and the spirit of the time

Some fragments have been lightly edited for clarity.

I never knew my grandfather on my father’s side - Bogdan.

His presence, and whatever work he did, lived in family memory only as fragments, half-told stories.

But one line always came back: “Granddad Bogdan worked in Miastoprojekt.”

For a child, that sentence meant little more than saying someone was a teacher or a policeman. It was just a label - a profession.

It wasn’t until I went away to study architecture that my family finally began to talk - about his engineering career, and about that world I had known only by name.

And, as it turned out, one of my grandfather’s old colleagues - who had worked with him in that same Miastoprojekt - lives just around the corner from my grandmother.

And he’s an architect.

I asked for a meeting.

Not only because I wanted to learn more about my grandfather, but because architecture created under the communist regime - in the time of the Polish People’s Republic (PRL) - belonged to a completely different creative and political reality.

July 2019.

A little bit overawed… I sit across from Mr Adam Kołodziej.

I’d asked him for a conversation I could record.

I had no plan - no list of questions. It wasn’t meant to be an interview.

It was meant to be a conversation about a reality that no longer exists

but one that, in a tangible and literal sense, shaped mine - our - spatial reality.

I wanted to hear his story.

The story of how it was.

How one created in the iron times… how one created when politics seeped into every corner of life,

when creativity itself was under strict control.

The weight of memory

“For a long time, I hesitated. It felt like mourning… but then I thought: who’s going to care when I die?”

Adam Kołodziej : Together with my wife, we are at the stage of putting our life in order.

There comes a moment when a person starts to say goodbye - not in a dramatic sense, rather in a systematic sense.

Lately, I’ve been analysing different ‘eras’ : pre-computer era, when everything had to be done by hand - on tracing paper, with a Rotring pen, before that a rapidograf, and before that, with a grafion…. For you this must sound like ancient history, young people today don’t know what a grafion was.

( Mr Kołodziej was right, I didn’t know).

Those were long years…. Painstaking work, drawing projects day and night all by hand on tracing paper.

First at Miastoprojekt - where my early projects… well, unfortunately, to put it plainly, they all went to the dump.

Literally. Gone. Thrown away, into the trash.

Only the later projects survived, from after 1985, when I set up my own private design studio. At the Studio of Fine Arts, where I also worked in the same time, whole drawers were filled with those drawings, translucent sheets.

I started going through those drawers, month after month - destroying those papers and throwing them away, one by one.

Sara Kazuro: Oh, That’s really such a shame…

Adam Kołodziej : It took me a long time to let go of it all. A very long time. I hesitated. It felt like mourning. But then I thought:

“Who’s going to care when I die?”

My son, Jacek, he won’t take all those scraps. Besides - he has a completely different outlook. Very critical of what we did.

Because he doesn’t understand the conditions we designed in - how different the reality was back then.

We worked inside a system, within restrictions, but always with a hunger to do more than seemed possible; to raise the bar as high as we could. Regulations, materials, construction methods - everything was different. Harsh. Meagre.

But we wanted to smuggle in quality.

Footnotes for technical terms

Grafion – an old-school drafting tool, basically a metal nib with an ink reservoir, used before technical pens were developed. Extremely precise, but messy and slow.

Rapidograph – an early refillable technical pen (by Koh-I-Noor or Staedtler), used widely in the mid-20th century for technical drawings. Produced uniform line thickness, but very prone to clogging.

Rotring – German brand of technical pens that replaced rapidographs in many studios. More reliable, became standard for architectural drawings until digital CAD systems took over.

Tracing paper (kalka techniczna) – thin, translucent paper used for copying and layering drawings. Every iteration of a plan had to be re-drawn by hand on this paper.

Chapter 1: Creativity in the Iron Times - Dare you say… Bauhaus?

Sara Kazuro : That’s exactly what brought me to you. On the one hand - the story of how architecture was created in those times.

On the other - how politics crept into the creative process. And then how everything flipped upside down after the system changes. Could you sketch it out for me?

Tell me the story?

Adam Kołodziej: All right. Let’s start from the beginning… with my studies.

I studied in Gdańsk, at the Faculty of Architecture.

At that time, there were only four such faculties in the whole of Poland - Kraków, Warsaw, Wrocław, and Gdańsk. Getting in was incredibly difficult: six, eight applicants for one place.

It really was the elite.

Our faculty was special. We had a lot of drawing and painting- real, serious work.

And the real sensation at the Polytechnic was this: we, the architecture students, were drawing nude models!

But it wasn’t any kind of whimsy - it was proper artistic training. Four semesters of sculpture. Busts, reliefs, abstract spatial forms. It was an approach more like an art academy.

We were taught by the old masters - professors from Lwów and Wilno, educated before the war. After the war, they had settled in Gdańsk and took an active role in rebuilding the city.

Their experience and their demands were immense. That’s why we had brutal exams in the history of architecture. But at the same time—they placed the highest value on creation.

The idea, the act of creation - that was what mattered most!

I joked: Sounds a lot like Bauhaus.

Mr. Kołodziej smiled slightly and said:

“In those days no one would have dared say that out loud. But yes - that was the spirit of Bauhaus.”

Adam Kołodziej: Back then it was all about craftsmanship. Everything! At university we got used to doing every single thing by hand, on bristol board. All our drafting technique was done that way. Tracing paper was only for concepts, for corrections - you’d smudge things in pencil,

Later came a miracle - felt-tip pens, colored pencils……

I remember the very first lettering class… where they taught us thousands of different typefaces: Gothic, Roman capitals. Endless, nightmarish exercises!

The assistant began with instructions :

“When you buy set squares, you place the triangular one against the drafting machine, draw a line, then flip it over—if it doesn’t match, throw it out!”

“When you sharpen pencils - either to a point or to a chisel edge. There are pencils B1, B2, B3, H1, H2—each for a different use.”

“How to draw with a match dipped in ink. How to write with the stick from a Calypso ice cream…”

And exercises at home…. every single time, damn it! He’d give us more homework!

At home we had to fill whole sketch blocks with lettering - you had to write compositions in Roman capitals, or majuscule, or some other alphabet. Good practice if you ever wanted to design tombstones….

And that’s not even counting other assignments like designing a book cover… he would hand out topics at random :

“You, sir - glass. You, sir - wood…”

I’ll never forget - my friend Jacek, the one I was close with (he’s now a professor at an architecture university in Canada), he was assigned “wood.” SO… on his book cover, he drew… a coffin.

And that’s how they released us into the world - idealists, really.

We had no idea what daily work as an architect in the PRL looked like. Sure, we did construction practice a couple of times. We went on outdoor painting trips, measured and documented historic buildings -Toruń, for example. We sketched, measured, photographed.

But what work in design office actually looked like - nobody showed us.

After graduation, my wife and I moved to Toruń - her family was there. At that time… the demand for architects was so high you could literally “sell yourself for an apartment.” The construction consortium took us immediately.

My wife stayed home with our little daughter, who was born in our final year. Later she went back to work - she even worked on the design of Elana [the textile factory].

As for me - to get my professional license, I had to spend a year and a half on a construction site.

I was site engineer for the Helios Hotel and the Książnica.

I had absolutely no idea what I was doing….

But I was lucky - there was a Majster - the foreman who took me under his wing.

He taught me everything - how to run a construction site, how it all worked “behind the scenes”. He was my first real teacher of the profession.

Chapter 2: Entering the Profession - The Road to Miastoprojekt

Adam Kołodziej.: After working on the Helios Hotel and the Książnica library - where I really did learn a lot - the atmosphere started to sour. A handful of young people with higher education came into the Kombinat, and suddenly I was the only architect among them. The rest of the staff were seasoned building technicians. You could feel the tension right away.

It all got political. And unfortunately, I got caught in the crossfire. They moved me to smaller, less ambitious projects.

First I ended up on some dull construction site on the edge of Toruń.

One-story industrial sheds. Absolute boredom. Empty… with mice running around my office.

That was the time I began seriously trying to get into Miastoprojekt.

What helped was a chance encounter with Tadeusz, a structural engineer from Miastoprojekt - later a close friend. We ran into each other on a train from Warsaw.

He knew me as being, well, “a pain in the neck” - in other words, very precise.

Once, I had caught a mistake in documentation that could have led to a construction disaster.

I basically saved the project! He said to me then:

- “Well, why don’t you come work with us?”

And that’s how I found myself at an interview in Miastoprojekt.

I already knew them all from SARP (the Association of Polish Architects) - back then there were maybe ten, twelve architects in all of Toruń.

The director looked at me and simply said:

“Alright, why don’t you join us”

So I resigned from the Rural Design Office - where I had been doing uninspiring projects for collective state farms - and I joined Miastoprojekt.

I ended up in the very same studio where your grandfather, Bogdan, worked.

And I stayed there for almost twenty years.

Chapter 3: The Centralisation of Creativity - Miastoprojekt, Prefabs, and the ‘Plomba’

Miastoprojekt - literally “City Project,” the state design bureau network in communist Poland

‘Plomba’ - an architectural term for an infill building, filling gaps in existing urban fabric

Adam Kołodziej : The Miastoprojekts were organised all over Poland as specialised design offices.

Our focus was the city — urban design and architecture.

The Miastoprojekt in Toruń was one of many bureaus across the country. Each region had its own, all subordinate to the Central Office in Warsaw, on Wierzbowa Street.

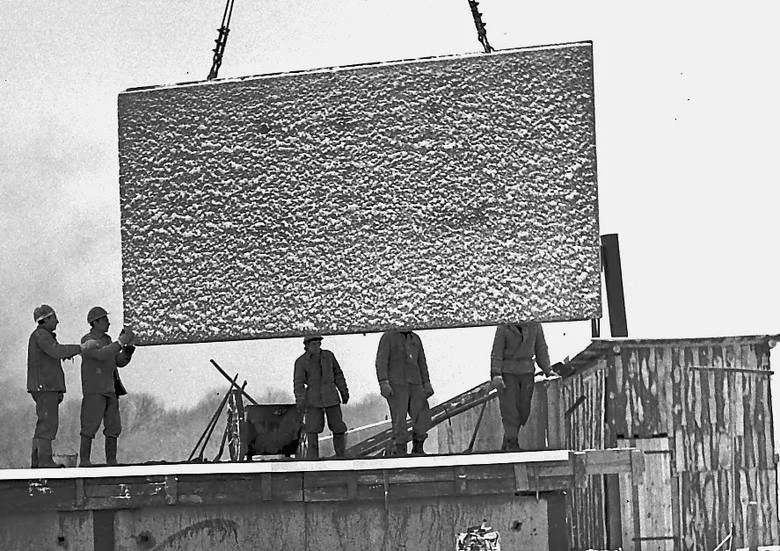

That Central Office in Warsaw handled all the prefabrication systems - OWT-67, OWT-75, WK-70.

That was what we called the “Great Panel” system - the prefabricated concrete panels everything was built with back then.

They developed all the working drawings.

On that basis, a ‘house factory’ was set up in Toruń, producing prefab elements based on Warsaw’s designs.

Forms, molds, production lines - everything was engineered there.

And yes, all those buildings ended up being identical, made with the same technology.

Our job, as architects, was to “plant them” into the urban context - to ‘compose’ the neighbourhoods, adapt the catalog buildings to local conditions, and make them fit the terrain.

The “Great Panel” system (Polish: Wielka Płyta) - a standardised large-panel prefabricated concrete construction method used across socialist Poland in the 1960s–1980s. Entire housing estates were built from identical factory-made panels, reflecting both industrial efficiency and the ideological pursuit of uniformity.

A.K.: In Miastoprojekt, the teams were mixed, both technicians and architects worked side by side - and, a huge part of the team were women.The ratio was usually something like : me as the General Designer, and six or eight women, that was my team.

Most of the building technicians were women, but we also had women architects.

“And they certainly didn’t earn less than us - absolutely not!

Were they less respected?

God forbid !

They were just as important as we were.”

The hierarchy in the design offices was rigid and I used to joke that it was like in the army :

Someone with a technical diploma was a technical assistant.

Then came assistant designer,

then senior assistant,

then designer,

then senior designer,

and finally chief designer.

And at the very top of the ladder was General Designer.

There were maybe fifteen, twenty of those in the whole country.

When I finally reached that title, it came with a mountain of administrative and organisational responsibility.But to stay sane I made one condition:

I am still going to design.

Around that time, in Toruń, the president of the Kopernik Housing Cooperative started a new trend.

He wanted “plombas”. This meant new ‘infill’ buildings squeezed into empty lots between older ones, mainly in the city center.

A.K : Designing those was more relaxed.

That president wanted them to be showy -‘exclusive apartments’.

Everywhere else we were watched like hawks with Regulation 110 - no apartment could be bigger than 48 square meters, period. In those blocks it was strict.

But here? We could, with trembling hands, sneak in three square meters more… five square meters more.”

Those apartments were intended for people the president had close ties with - the nomenklatura.

S.K. : Meaning the Party elite?

A.K. : Exactly. “The Party” meant the Communist Party - the one and only political structure back then. People tied to it had privileges: better apartments, car vouchers, access to goods and opportunities that ordinary citizens could only dream of. Those were the people we designed the “luxury” infill buildings for.

S.K. : So would you say that with designing plomby you had more creative freedom?

A.K. : Yes, there was a bit more creative freedom… if you can even call it that.

But above all - people today have no idea what kind of reality we were forced to work in. It was mad poverty - not just lack of money, but the kind imposed by the system itself.

And on top of that - we had no idea what was happening in the world!

We were completely cut off - no news, no trends, no sense of what architecture was becoming anywhere else.Today, you open ArchDaily and the whole world is at your fingertips.

Back then, nothing.

The only ‘western’ magazine you could buy at the kiosk was Bau-Majster, and there was nothing exciting in it.

No one was allowed to freely travel abroad.

The first time I went, was with the Architects’ Association - to Finland. And after that trip, some of my colleagues said:

‘That’s it, I quit designing!’

A.K. Ahhh Finland in those times… a fantastic country. The houses there-single-family, beautiful, so natural. Even now, we still haven’t caught up to that level!

But later came the reflection - if we could have imported those materials, the timber, the clinkers - we might have done something like that too.

But we simply had no access to anything!

So everything was prefabricated. Boxes. As cheap as possible.

There were only two window factories in Poland. Catalogs: O1, O2… up to O35. The same windows went into towers and into family houses.

All the schools from that era - the same windows.

Once, I insisted on making a two-meter-wide double door opening. I designed the doors myself.

And because it was for a plomba, they let me…I Found a little carpentry shop, and they built them out of whatever they had on hand!

S.K. (thinking) - ‘Architectural rebellion’

📌 Why was there “mad poverty” in the PRL, and no access to modern materials?

Because Poland was a centrally planned economy, part of the Eastern Bloc, sealed behind the Iron Curtain. Contact with the West was blocked. Hard currency was scarce, and any imports went to heavy industry or the military - not housing. Prefabrication and standardisation were the rule. Travel abroad required special permits, usually only for athletes, artists, or official delegations.

Result: architects worked with the same narrow set of materials and catalog elements, learning about world trends only from a rare magazine or a tightly controlled study trip.

📎 Context:

Under the communist regime, architecture operated within the framework of a centrally planned economy.

All building materials were state-controlled and strictly rationed, imports were practically non-existent, and access to foreign publications was limited to a handful of technical journals.

Even the simplest design decisions - such as adding a window type or changing a door dimension - often required negotiation, improvisation, or quiet acts of defiance.

Adam Kołodziej: On Słowackiego Street there’s one of my plomba-buildings - one of the vestibules there is all in wood…

Every section drawn out directly for the builder - they were very detailed drawings.

Some details we drew at 1:1 scale - otherwise people would go blind trying to read them!

There were no photocopiers…

Everything went to the blueprint lab, onto light-sensitive paper, developed in ammonia - the so-called ozalid copies.

Technical descriptions were written by hand, and then the ladies in the typing hall would type them up in several copies:

one for the archive, one for the site, one for the inspector of works…

The whole machinery of it.

A.K. : We actually earned quite well. We were organised in a kind of capitalist way - there was the “output” and a bonus system.

But the bonuses had to be divided - between the various technical branches, between the members of the team.

And that’s where the fights always started…

Eventually, I came up with a mathematical system, set the proportions with the team - and that was that - Peace restored.

That’s how it all worked - in very broad strokes.

A.K. : And it was around that time, with your grandfather Bogdan, that we first started thinking maybe it was time to move out of those blocks…

That’s how our first conversations began. We even had a plot in mind, but it fell through.

We wanted to build ourselves - as a group.

It wasn’t us that failed, you see - it was the whole arrangement, the permissions, the dependencies…

So in the end it didn’t happen. And good thing, really - better that way.

Later came a commission - for these houses here. Right where we’re sitting now.

That was 1974.

The design work started, and Bogdan said:

Listen, maybe you could try your hand at these houses?

And I said: Why the hell not, all right - I’ll give it a try.

I have set up a meeting with the director of Elana.

I offered that, as a social initiative, we’d do the designs cheaper, but I wanted to reserve a place for my design team. He agreed! And… here we are.

Of course, there were some adventures along the way…

Solidarity took an interest in us : Beneficiaries! While the working class goes unnoticed!

But the director was strong enough, politically, that nothing happened to us.

Later, during martial law, that old Party hardliner - Comrade Siwak - turned his gaze on us again.

Then came the system changes, privatisation… loan repayments…

But we managed to sail through all those reefs.

And that’s why we’re still here.

“Well…(mr Kołodziej smiled) but it wasn’t only plomba-builds we were designing back then.

Actually, that’s when I got tangled up in the whole Rubinkowo story.”